Egress is a means of emergency escape. Not surprisingly, all houses need egress for events such as a fire, and emergency egress is required by the International Residential Code for residential buildings. The IRC requires a form of egress in basements and rooms where people sleep. Each bedroom must have its own emergency exit.

Egress is a means of emergency escape. Not surprisingly, all houses need egress for events such as a fire, and emergency egress is required by the International Residential Code for residential buildings. The IRC requires a form of egress in basements and rooms where people sleep. Each bedroom must have its own emergency exit.

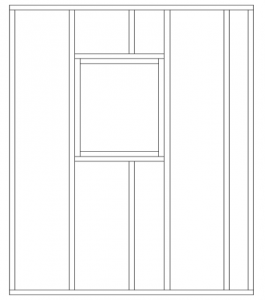

While egress could be a door opening to the outside, it is most commonly a window, and the IRC specifies minimum requirements for egress windows. For one, an egress window needs to open to a public street, alley, yard or court. Also, the window must meet minimum size requirements so people can exit. The minimum size is 5.7 square feet, unless the windowsill is on the floor, in which case the minimum is 5 square feet. The window must be at least 2 feet tall and 20 inches wide. Meeting the minimum height and width requirements doesn’t guarantee meeting the minimum area, so the window will have to be larger in at least one of those dimensions.

Finally, the window cannot be more than 44 inches from the floor, and people must be able to open the window without any special tools or knowledge. Window coverings, such as a screen or bars, are OK, but people need to be able to remove them without any special force, tools or knowledge.

Basements are often located below grade, or below the typical ground level. Since egress windows in basements wouldn’t do much good opening to soil, a window well is required outside the window. The window well should be large enough for the window to open fully, and also should contain a ladder if the well is more than 44 inches deep. Of course, the IRC specifies well and ladder dimensions if this situation applies to your home.

Does your house have emergency egress? Some older homes built before the IRC requirements do not. A means of egress is sometimes overlooked during remodels — for example, converting a space to a bedroom that was not initially planned for that use. If you have a room that does not meet the minimum egress requirements, there are many reasons to correct the problem, the most important being providing a way to exit a house safely in an emergency.

Adding egress windows in required rooms will allow your house to pass inspection should you decide to sell it and will add value to the home as well. Sometimes, adding or replacing windows can become a major project, and it must be done correctly to avoid air leakage and drainage problems later. If you need to install egress windows, find a contractor familiar with the building code and who will take the time to properly install energy efficient windows that meet the requirements.